Table des Matières

Search

Website Design and Content © by Eric Krause,

Krause House Info-Research Solutions (© 1996)

All Images © Parks Canada Except

Where Noted Otherwise

Report/Rapport © Parks Canada / Parcs Canada

---

Report Assembly/Rapport de l'assemblée © Krause

House

Info-Research Solutions

Researching the

Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada

Recherche sur la Forteresse-de-Louisbourg Lieu historique national du Canada

PRINCESS

BASTION REPORT:

A SURVEY OF THE AREA FROM THE RIGHT REENTRANT

ANGLE OF THE PRINCESS BASTION TO THE RIGHT REENTRANT

ANGLE OF THE BROUILLAN BASTION, AND THE RELATION OF THIS

AREA TO CAP NOIR

BY

MARGARET FORTIER

February, 1966

(Supervision: W. Stevenson, J. Hanna)

(Fortress of Louisbourg Report H B 3)

Presently,

only some illustrations are

included here.

For all of them , please consult the original report in the archives of the Fortress of Louisbourg

![]() Return/retour

- Table of Contents/

Return/retour

- Table of Contents/

Table des Matières

SECTION II

CHAPTER 5

Crenelated Wall

As was said in Chapter 3, the French looked upon everything from the retired battery of the Princess Bastion to the salient angle of the Brouillan Bastion as the Crenelated Wall. However, since they formed one half of the Brouillan Bastion, the right face and flank of the latter will not be dealt with at this time. For the purposes of this report, therefore, the term Crenelated Wall will refer to the small left face and flank of the Princess Bastion and the curtain between it and the Brouillan Bastion. The latter section will be referred to as the crenelated curtain.

CRENELATED WALL and CURTAIN

Although to begin this section by treating the crenelated curtain breaks the counterclockwise pattern thus far followed in dealing with parts of the Princess Bastion, it is the most logical way to proceed. The curtain was the wall usually meant when the general term "crenelated wall" was used. It is only about this section that anything concrete may be said regarding construction. It would be impossible to describe the small left face and flank without a prior knowledge of the curtain.

From both documents and plans, it becomes evident that with the Crenelated Wall it is possible to project backwards to a larger degree than with any other section of the Princess Bastion. That is, it is possible to use information from a year late in the Wall's history to recreate a picture of the original wall. For, though no area was talked about more by concerned Governors, Intendants and Engineers, no area was altered less.

The landward fortifications from the Dauphin Bastion to the retired battery of the Princess Bastion had been considered to be part of the "Enceinte de la Ville". Despite the considerable amount of work to be done, the city could be thought of as closed on its landward side by 1738. However, the northern and eastern sides of the city, those facing the sea, were as yet unfortified. Plans were made for a "Nouvelle Enceinte" which would close off the seaward fronts. This enceinte, which would begin at the retired battery of the Princess Bastion, came to include the Crenelated Wall, the Maurepas and Brouillan Bastions, and the Piece de la Grave.

The land on which the Crenelated Wall was to be built had been occupied by a cemetery. [154] After some deliberation, it was decided that the cemetery should be moved outside the city. The areas before the Porte de la Reine and the Dauphin Bastion were suggested. [155] but a spot somewhere in the environs of Cap Noir was decided upon. [156] Work was done on the Crenelated Wall during 1739, and it was completed that same year. [157] In 1740 the Minister wrote expressing his pleasure over the Wall's completion. He noted. at that time that it was reveted in planking, and its summit was covered with shingles. [158]

This reference was one of many which gave such incomplete information. From these scattered references, the Crenelated Wall emerged with certain characteristics:

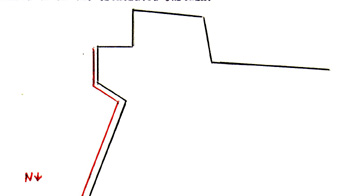

1 - It had a masonry core which was covered over on both sides with wooden planking. [159] (Figure 16)

2 - The summit or "roof" of the wall came to a point on the top [160] and was covered with shingles.[161] (Figures 11, 16 and 24)

3 - The crenelations were rectangular in shape - long on the sides; narrow on the top and bottom. They were located in the body of the wall itself, rather than along the summit as are most crenelations. Intended for small arms or musket fire, the crenelations were not very large. Their exact measurements, however, are unknown.[162] (Figure 16)

Finally, a complete description of the Wall's construction was recorded in the report on the demolition of the fortifications in 1760. It was then stated that uprights of oak, measuring 8 feet, by 8 inches, by 6 inches, were placed perpendicular to the wall during its construction. Probably, these were imbedded in the masonry in the manner described in the discussion of the eperon and the projected works of 1749. The uprights were spaced about 6 feet from one another on both sides of the wall. Beams measuring 4 feet, by 8 inches, by 6 inches joined the uprights together. They were placed at intervals of 4 feet. This frame was then covered with planks 12 feet, by 12 inches, by 2 inches. [163]

For added strength, palisades were positioned on top of the wall, nailed to the planking on the outside. [164 ]This work was probably done during the first siege when pickets were said to have been put on the low wall to raise it to the height of the others. [165] Estimates of the height of these palisades ranged from five to eight feet. [166] The wall itself had no rampart, [167] but was backed by a banquette. [168]

The question of height, as far as this wall was concerned, was a most important one. Everyone agreed that it was too low, and from the time of its completion forward, was attempting to remedy or take advantage of - as the case may be - this defeat.

There is no way to determine the exact height. of the wall. A 1737 profile showed the projected wall to be higher on the inside 12 pieds (scaled) - than on the outside - 10 pieds. [169] (Figure 11) In 1745 an Englishman reported the height of the wall to be somewhere between 12 and 16 feet. [170] Another profile, this time from 1751, presented the wall as being higher on the outside - 11 pieds 9 pouces as opposed to 6 pieds 8 pouces above the banquette on the inside. The banauette itself was 3 pieds 6 pouces above the interior of the place. [171] Lastly, Bastide declared in 1758 that the wall was only 7 feet high. [172]

It would seem strange that a variation of 5 feet would exist in estimates of the height of a wall so low that five feet would make a considerable difference. However, judging from comments concerning the deposits of sand and gravel before the whole seaward front, this is not really so unusual.

In 1744 work was done toward the removal of gravel which the sea had carried to the foot of the Crenelated Wall. [173] This was the first mention of the accumulation of gravel and sand in this area. Seven years later Franquet wrote that the terrain in front of the Crenelated Wall was a beach which was large in some places, small in others. This beach, he said, rose so considerably in spots that it made access to the Crenelated Wall very easy. One of the works he wished to see provided for that year was the removal of the gravel. [174] In another report he stated that the easy accessibility offered by the deposits of from 5 to 6 pieds made the Crenelated Wall the only section of the seaward front susceptible to surprise attack. [175] It was reported in 1754 that, on the outside, the crenelations were on the same level as the beach due to the sea's deposits. [176] It is not too surprising, therefore, that at different times the Crenelated Wall could appear much lower than it would have a few years earlier or later.

As was said, the first removal of the deposits from in front of the Crenelated Wall took place in 1744. At that time dimensions were given for the areas worked on, but it would appear that they did not coincide with the parts of the Wall. Three sets of dimensions were listed, and there were three main sections of the Wall. However, the lengths set down could not possibly have corresponded with those of the sections. For example, a length of 94 toises was given in one of the sets. This would be much too long for the face and flank of either the Brouillan or Princess Bastions since it was more than the length of the face and flank of the King's Bastion. The total length was 233 toises 7 pieds a figure which may have equaled the total length of the Crenelated wall. [177]

The last major dimension - width - is no more exact than the other two. In the course of the years from 1737 to 1758, the thickness of the wall was mentioned at least eight times. Though the thickness was probably taken at various places along the Wall, the appraisals were fairly consistant:

1737 - 3 pieds [178]

1745 - 6 feet [179]

1751 - 2 1/2 to 3 pieds [180]

1751 - 2 pieds 8 pouces [181]

1757 - 4 1/2 pieds [182]

1758 - 2 pieds [183]

1758 - 2 pieds [184]

1758 - 2 1/2 feet [185]

It might be assumed, if only on the basis of a numerical average, that the Crenelated Wall had a thickness of between 2 and 3 pieds.

Whatever guessing right be necessary to arrive at an accurate set of measurements, one thing is certain; the wall was too low and too narrow to satisfy officials at Louisbourg, French or English.

In 1744 a dispute arose between Verrier and DuQuesnel concerning the value of a ditch in front of the Crenelated Wall. Verrier opposed the ditch because he felt that it would serve no useful purpose, and would be harmful to the flanks which had to defend the wall. He did not elaborate on this last statement, but he did say that the three pieds difference in height provided by the ditch would not make the wall any less vulnerable to an escalade by the enemy. Rather, he felt that the Wall itself should be raised 6 pieds. This would not simply make it harder to climb, but it would also create a greater drop into the city. If the enemy had ladders, he reasoned, they might easily scale the wall, but the jump down to the banquette from the heightened wall could not be made without injury, and, the French would have time to overwhelm the attacker before he had recovered his footing. [186] (Figure 16)

A detailed estimate of the cost of Verrier's project gave the total figure as 10849L. This included expenditures for earth to fill in the parts of the ditch (ordered built by DuQuesnel and which Verrier showed on a profile to be awaiting refill [187] not filled in by the sea; masonry; pine woodwork; planking; and boards from Boston. [188] The project was never carried, out. However, permission to raise the wall was granted by the home government, ironically enough, while the city was under siege.[189]

The French had some reason to worry about the wall because they were not alone in the opinion that it might easily be scaled. While planning their attack on Louisbourg, the English considered taking advantage of the low wall as a good means by which to enter the city. [190]

During their stay at Louisbourg, Knowles and Bastide wrote that the Crenelated liall was an "exceedingly bad piece of work and must be made into a proper curtain". [191] They were obviously as unimpressed with the Crenelated Wall as they were with the Princess Bastion itself. There is no indication, however, that they made any attempt to improve the situation.

When, upon their return, the French began considering ways of strengthening the city's weaker points, the Crenelated Wall came in for much discussion. Not only was it frontally vulnerable, but it was also susceptible to the fire from Cap Noir. Franquet declared that if no redoubt was placed on the hill, the Crenelated Wall had to be reinforced. [192] His plans for reinforcing it were elaborate. The small thin wall was to be replaced by a massive structure which would require the building of contreforts behind the revetment. A rampart would be constructed, and a terreplein and banquette formed. [193] (Figure 24)

|

* Dimensions scaled |

pieds | pouces |

|

Exterior revetment - height above base Revetment - width at summit Contrefort - width Exterior slope of the parapet - height Exterior slope of the parapet - width Superior slope of the parapet - height Superior slope of the parapet - width Interior revetment of parapet - height Banquette - width Slope to banquette - height Slope to banquette - width Terreplein - width Interior slope of rampart - height Interior slope of rampart - width |

18 5 6 2 1 2 12 4 6 *3 6 12 3 8 |

- 6 - - 6 - - 6 - - - - 6 6 |

In Franquet's various projects, as evidenced by the plans, this scheme can easily be seen as the crenelations and simple banquette disappear and are replaced by an obvious representation of much stronger works. [194] (Plates 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13)

During 1751 the Minister wrote that the Crenelated Wall was without a rampart, very badly flanked and too low. If they had had to build this kind of work, he felt, they should have extended it around Rochefort Point to the Piece de la Grave. The city would have been rendered much stronger and the cost would have been no more than that expended for the maintenance and repairs at the Brouillan and Maurepas Bastions. Though he was of the opinion that sooner or later such an extension should be made, for the present he ordered that the wall be remade along the lines suggested by Franquet; that is, it should be raised (an escalade being all it had to fear), and it should not be thickened since it was not open to artillery attack. [195]

This last statement, credited to the Engineer, is completely at variance with the projects drawn up by him and submitted to the Court. Yet, it does seem to represent Franquet's thinking on the subject. He declared that the seaward front could not be attacked from the sea because the ships could not come close enough, and 100 guns would be deployed on the front to fire on any ships attempting an attack. Neither was this front susceptible to a coup de main since the enemy could not but help to announce themselves when they tried to land in the cove. Only the Crenelated Wall might be surprised, he felt, because its low elevation was an invitation to an assault. [196] Raising the wall, therefore, would serve to remedy the existing defect. No massive structure would appear to have been warranted if this line of reasoning were followed.

The wall had to be raised, but its height had to be kept below that of the salient angle of the Princess Bastion. For, Franquet explained, too much elevation would cause the wall to be enfiladed from the rear. While the wall was being raised, the gravel had to be removed from in front of the wall to lessen the chances of an enemy attempting to scale it. If, for added strength, they decided to widen the rampart 12 pieds - a thickness considerably below the figure projected in the profile -Franquet intended to lower the parapet so that artillery might be placed there and embrasures might be opened where needed. He did not agree that the wall should be extended along Rochefort Point since erosion was taking place too fast to make that necessary. [197]

Apparently, Franquet had suggested making provision for musket fire to guard against an enemy's advance toward the Crenelated Wall from the foot of the left face of the Princess Bastion. In 1753 the home government wrote that in their opinion this plan was "mediocre" and that such a mmaneuver on the part of the enemy could be prevented by fire from the Brouillan Bastion. [198]

The plans of 1755 which were intended to show the works ordered by the King depict the Crenelated Wall without crenelations and with a rampart as Franquet had represented it in the plans of 1751. [199] (Plates 10, 11, 12 and 13) However, the following year it was stated that the Wall was in the same state as it had been at the restitution of the Fortress. [200]

It was felt that if the Crenelated Wall was attacked, it would be best to defend it with quick force, preferably from the small left flank since it could be seen only from the sky. This would be most effective because the enemy could land only at low tide and only after clearing the chevaux de frize that the French proposed to put in the harbor a little short of the shoulder angle of the flank. [201] Quick action against an enemy hindered by natural and man-made obstacles would give the French a decided advantage.

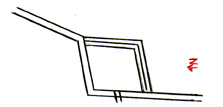

Some time during 1757 two capomieres were constructed

at either end of the crenelated curtain. Their purpose was to

defend against a descent from the cove where it was feared the

enemy might land. [202] The caponnier on the north end of the

curtain was said to be capable of holding 300 men.

[203] Trapezoidal

in shape, this caponnier extended from a point on the curtain to

the shoulder angle of the Brouillan Bastion. Its parapet was

made of sod, and a banquette had been formed. The caponnier's

glacis was made of shingles and partly covered with earth which

might easily be washed away in a storm. There was no outlet

through which water might drain. [204]

The caponnier on the south end was smaller, owing to the need to obscure it from the view of enemy fire on Cap Noir. [205] Its parapet was reveted with fascines, and the glacis was made of shingles and stones. Triangular in shape, this caponnier extended from the crenelated curtain to the "shoulder" angle of the Princess Bastion. Palisades and a banquette had been provided for at this caponnier also. No drain was built to allow water to flow from the caponnier, and a pond, situated directly behind it, periodically overflowed filling the interior of the caponnier up to its banquette. [206]

Both caponnieres were entered through posterns opened in the crenelated curtain. From the plans, it appears that the postern into the south caponnier led directly into the pond mentioned above. [207] These posterns were fortified by herses [208] after the fashion of those used at the passages of the gates of the city. [209] (Figures 31, 32 and 34)

In 1758 little was said about the condition of the east side of Louisbourg. Apparently none of the fears held by the French were realized. One reference did state that the sick and wounded, in tents near the Crenelated Wall, were continually "raised" by the cannon and bombs of the enemy, indicating that shots were falling not far from the Wall. [210] There is no record, however, of the Wall having been hit. The English reports would seem to indicate that the crenelated curtain was in good condition when they entered the city. [211]

SMALL LEFT FLANK and CAVALIER

Built at the same time [212] as the curtain, the small left flank probably differed only in its length and direction. Nothing was said of the wall to distinguish it from the one to which it was joined. In 1745, when the English were planning their projects at the Princess Bastion, the flank received its first notice, albeit in a negative way. According to the proposed scheme of things, a new left flank would be built connecting the crenelated curtain and the new left face. [213]

It was reported in 1749 that the angle of cut-stone of the small left flank - whether shoulder or reentrant is not known was defaced from 1 pieds deep at its foundation to a height of 6 pieds due to the beating given it by the sea. [214]

When concern over the possibility of a descent from the cove began to grow, awareness of the small left flank did likewise. Franquet declared in 1751 that it was the only part of the Wall able to defend the seaward front. especially in the event of an escalade or a breach in the Brouillan Bastion's right flank. Fire from the small left flank, it was felt, would hit any troops attempting to enter that Bastion. [215]

Plans were made to "mask" the crenelations of both the small left face and flank. [216] It would seem that the French were intending to change the nature of the two walls by doing away with the openings and remaking the face and flank in the manner described in relation to the crenelated curtain. (See page 40 of this Chapter) The plans of Franquet's Projects bear this out. [217] (Plates 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13) The list of expenditures necessary for this project also included materials required for the thickening of the small left flank's interior revetment, the raising of the flank 3 pieds, and the forming, of a banquette. The needs of these projects, as shown on the list, were not excessive. Only 30 cubic toises of earth at 9" and 12 cubic toises of masonry at 125" were requested. The total expense would have been 11770". [218]

If a report made in 1754 is creditable, it would appear that some repairs were necessary at the small left flank. At that time a witness stated that the left flank was so in disorder that any cannon fired at or from this wall would cause it to fall in rains. [219] No mention was made subsequent to that date of plans to repair the wall, but Franquet did emphasize its importance in warding off an enemy descent. [220] Therefore, it may be assumed that the account given was an exaggeration, or that, between 1755 and 1756, some form of repair work had been carried out.

The number of openings along the sections of the Crenelated Wall is a mystery. The plans vary greatly in what they show. While it is not feasible to count each of the crenelations in the crenelated curtaing it is not difficult with the small left face and flank. Of the 25 plans on which the crenelations appear in the small left flank, eight show 5. Taking all 25 plans, the variations are: [221]

| Number of plans | Number of crenelations |

|

8 4 4 2 2 2 2 1 |

5 7 9 3 6 8 10 2 |

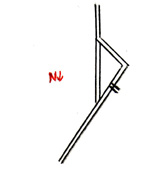

Behind the small left flank a cavalier was built in 1742-1743. This structure was raised in masonry to a height of 6 pieds in 1742, [222] and completed the following year.[223] Earth was brought in from elsewhere to form the platform of the battery. [224]

The first plan to show the cavalier in its place was drawn in 1744. [225] On this plan the cavalier is situated very close to the small left flank with little room allowed for the banquette which appears on most other plans.

Pierced by 4 embrasures, the cavalier was reported in good condition in 1751. There was only one fault. The fire from the cavalier was masked by palisades placed on top of the small left flank. These, Franquet stated, had to be removed so that the cavalier would provide cover for the beach and the right face and flank of the Brouillan Bastion, and better the terrain on Rochefort Point. [226] A 1758 view, rough though it is, shows pickets still present all along the Crenelated Wall to the retired battery. [227]

Plans were made during 1751 to raise the height of the cavalier some 3 pieds. For this work they required. [228]

49 cubic toises of earth at 9" ................................... 441: 0: 0:

7 cubic toises of masonry at 125" ........................... 237: 0: 0:

____________

1378: 0: 0:

The English realized the importance of the cavalier. When devising their plan of attack, they stated that the four guns of the cavalier had to be silenced before their troops might attempt a landing at the cove. [229]

Two accounts given in 1758 related that the cavalier had been constructed in order to batter the entrance to the cove since it was thought to be practicable for chaloupes. [230] Following the siege, the English reported that the escarp was covered with boards and seemed to be entire. The masonry of the interior revetment however, was "ruinous", and the parapet itself was very thin. [231] When the Fortress was taken, 4 six pound cannon were found at the cavalier. [232]

The statement that the cavalier was covered with boards was substantiated by the English Demolition Report. It declared that the structure was built in the same manner as the Crenelated Wall. The Report also pointed out that the earth near the cavalier was gravelly and mixed with stones, and that the structure was 88 feet long with a revetment 7 feet thick . [233]

SMALL LEFT FACE

This wall, which extended from the retired battery to the small left flank, presents a series of questions for which there are no answers. The early plans of the retired battery show it with a revetment on its left side which came to an end at the same point as the terreplein of the battery. In 1739 the wall was extended beyond the terreplein to form the left shoulder angle with the small left flank. [234]

Since this small left face was considered to be part of the Crenelated Wall, it would be reasonable to assume that the method of construction had been the same as it was at the other parts of the Wall. However, it is likely that this section was different in some way from the rest, owing to its original place as part of the retired battery. It is doubtful, for example, that this original section was planked on the inside, although the outside may well have received planking either during the initial construction or at the time the wall was enlarged. The extension of this wall was probably planked on both sides.

A problem related to the lack of information about construction of the small left face is the placement of the crenelations. It is difficult to determine whether they extended the full length of the wall or stopped at the beginning of the terreplein of the retired battery. It would, for a number of reasons, seem more logical that they did not go beyond the terreplein:

1 - According to the 1737, 1745 and 1751 profiles of the Crenelated Wall, the openings were not very far above the firing step.[235] If they continued along on pretty much the same level, they would be much too low to allow firing through them from the terreplein of the retired battery. This is especially so since the latter, it would seem from the plans, was higher than the banquette of the Crenelated Wall. [236] (Figures 13 and 14)

2 - The retired battery was not very large - 66 pieds long. It appears from a 1737 plan [237] that there was little room to spare when three cannon, set on platforms, and their crews were occupying the battery's terreplein. A 1751 drawing of the gun platforms at Louisbourg gave

the width at their widest point as 18 pieds. Multiplied by 3 this would be 54 pieds, leaving 12 pieds of free space. Since the 66 pieds was probably an outside measurement, it can be assumed that, allowing for the width of the wall, that the length of the terreplein was even smaller. The few feet left, therefore, had to be divided up four ways to permit some space between the platforms and the walls and the platforms themselves. The area left was not very large. [238] (Plates 2 and 3; Figure 25)3 - Because of the elevation of the terreplein of the retired battery, it might have been possible for men to fire over the wall without the benefit of crenelations.

4 - Since the part of the wall along the retired battery was built before the rest of the Crenelated Wall, it is not likely that openings were provided for at that time. It would seem foolish to rebuild a wall in order that a few openings be created, especially since the musket fire of a handful of men would add little to the security of the place.

5 - The evidence from the plans indicates that the crenelations stopped at the battery's terreplein. Only 11 plans show this to be the case, whereas 12 show them all along the wall. However, the quality of the 11 is much higher than that of the 12. Of the latter, 9 are English drawings which amount to little. They are rough sketches with few details. More than half do not even acknowledge the existence of the retired battery. [239]

The exact number of creneletions is another question. The following are the variations shown on the plans: [240]

| Number of plans | Number of Crenelations |

|

8 8 3 3 1 |

4 3 5 2 7 |

The problem of crenelations in the small left face is further complicated by the existence of many plans, among which are some of the most well drawn, which show the face with no banquette. The crenelations do appear on these plans, but there is no place shown from which a man might fire. This may be attributed to an oversight on the part of the artist who might well have assumed the continuation of a firing step along the entire length of the Crenelated Wall and saw no reason for showing one to the right of the cavalier. However, given the detail shown on some of these plans, this is not a completely satisfactory answer. There is no record of the banquette having been removed at any point, and the French gave no indication of the uselessness of this. (Figures 15, 229 31, 329 34 and 35)

In 1749 it was reported that the angle between the small left face and the retired. battery had several encroachments and total defacement of the masonry joints due to weather and lack of maintenance. [241] It was said that this wall could not be battered from the front since they had left only a small passage between itself and the wall. [242] Plans were made to reestablish the left face in 1757 so that it could not be destroyed from Cap Noir. [243] Work done to thicken it with earth, sod and fascines. [244] There was no report given by either the English or the French as to the condition of the small left face following the siege.