LouisbourgProperties Website Design and Content © 2005 by Eric Krause,

Krause House Info-Research Solutions (©

1996)

All Images ©

Parks Canada Unless Otherwise Designated

Report/Rapport © Parks Canada / Parcs Canada

---

Report Assembly/Rapport de l'assemblée © Krause

House

Info-Research Solutions

Researching the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada

~ Recherche sur la Forteresse-de-Louisbourg Lieu historique national du

Canada

REPORT 2005-64

THE BUILT HISTORY OF BLOCK

THREE, LOTS C, D, AND E

1713 - 1768

THE RÉCOLLET PROPERTIES

BY

ERIC KRAUSE

KRAUSE HOUSE INFO-RESEARCH SOLUTIONS

November 30, 2005

SELECT INTERPRETATIVE SUMMARIES - ABSTRACTS

INDEX TO SELECT ABSTRACTED REPORTS [To go to the abstract, click on the appropriate report]

(1) Adams, Blaine. The Construction and Occupation of the Barracks of the Kings Bastion. Unpublished Report H A 13 (Fortress of Louisbourg, July 1971) - Garrison Chapel

(2) Brenda, Dunn. Block 2, Lot G, Property of the Commissaire Unpublished report H D 14 R (Fortress of Louisbourg, 1969) - Genier and DeMesy

(3) Hoad, Lynda. Report On Lots A And B Of Block 3. Unpublished Report H D 16 (Fortress of Louisbourg, June 1971) - LaGrange and Beauséjour

(4) Hoad, Linda , Surgery and Surgeons in Ile Royale. Unpublished Report H F 21 (Fortress of Louisbourg, September, 1972) - LaGrange

(5) [Johnston, A. J. B]. A Louisbourg Primer. An Introductory Manual for Staff At the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site . Unpublished Manuscript 0 C 21 R (Fortress of Louisbourg, Revised March 1991) - Récollets

(6) Johnston, A. J. B. Religion in Life at Louisbourg 1713-1758 (Kingston, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1984) - Récollets

(7) Krause, Eric (Krause House Info-Research Solutions). Property Developments Fronting Rue Royalle And Rue D'Orléans (Including Rue D'Estrées And Rue Dauphine Fronting Block Thirteen) Louisbourg: 1713 - 1960. Unpublished Report HB701K72000 [2000-141] (Fortress of Louisbourg, August 21, 2000 (Revised December 11, 2004)) - Block Three, Lots C and D

Adams, Blaine. The Construction and Occupation of the Barracks of the Kings Bastion. Unpublished Report H A 13 (Fortress of Louisbourg, July 1971) [For the complete report, click on the title]

.... CHAPEL

A large double door from the central passage led into the garrison chapel. The nave of this chapel was only approximately 45 feet square, but since there were no pews in Roman Catholic churches of this period, the chapel could accommodate more people than its modest size would at first indicate. Complete details for the altar were not given and the two barracks floor plans (Figs. 9,10 [1724-1; 1725-3, 1725-3A: Presently Unavailable]) show differing schematic outlines for the structure. From the works accounts it is known that oak planks were used for the floor of the sanctuary as well as the chapel proper, and that one-inch pine planks were used in the altar, whose dimensions were just over 7 feet by 3 feet. Under the heading of "Fine Carpentry" in the work accounts were listed the pulpit, choir stalls and the frame of the picture which hung over the altar as well as the doors on either side of the altar. The door on the left led to the chaplin's room and the one on the right had given access to an officer's room but was later blocked in, although the door was retained to complete the symmetry of the front of the chapel. Behind the altar and the painting hung a printed cloth, and somewhere near the entrance was a holy water vessel supported by iron consoles.[1]

The reredos of the chapel was not finished until after 1726 and there were complaints that inferior wood had to be used and that there were not enough skilled workmen to do the job.[2] However, services were being held there despite the unfinished condition of the chapel.[3 - EDITOR'S NOTE: This source does not mention services being held] The furnishings for it had been in Louisbourg since 1724 and give an interesting view of church ornaments of the period (see Appendix III). During the second French occupation the altar was described. The structure containing the tabernacle spanned the length of the altar. Over the centre of the tabernacle was a niche flanked by hearts and angles. Inside the niche was a copper crucifix, another heart, and a Holy Spirit probably in the form of a dove. There was a cornice around the edge of the tabernacle and a framed picture of Saint Louis above it with at least one small drawer underneath it.[4]

The barracks chapel was originally intended only for the garrison. The civilian population attended services in the chapel of the Recollet priests while waiting for the construction of a parish church. The parish itself was given the name Our Lady of the Angels. It soon became evident that money for a parish church was not forthcoming and the priests decided to force the issue. They had given over their own chapel, they said, "out of simple goodness",[5] but they refused to any longer, thus compelling the Louisbourg officials to make alternative arrangements. The only other available chapel was that in the barracks which became the new parish church. The chapel retained its name, Saint Louis, and the parish was still that of Our Lady of the Angels.[6]

The date of this transfer seems most likely to have been 1735. In that year the parish register stopped using the term "parish and convent church" and just used "parish church." [7] There was considerable overcrowding in the chapel under this arrangement, especially when there were sailors in the port,[8] however, it served as the parish church for the rest of the French occupation in Louisbourg. As one of the centres of town life public notices were posted there.[9] Maintenance of the chapel was in the hands of the priests who made so many requests for furnishings that in 1732 De Mesy felt it would be best to give them an annual allowance;[10] in 1745 this amounted to 400 livres. ...

An interesting feature in the chapel was the discovery during archaeological excavations of five bodies buried beneath the floor (Fig. 20 [Presently Unavailable]). They were the bodies of the governor De Forant, the commandant Duquesnel, and two military leaders, Captain Michel de Cannes, a captain of a Louisbourg company, and the Duc d'Anville leader of an expedition to recapture Louisbourg in 1746. D'Anville died on the expedition and had been buried outside Halifax; in 1749 the body was reburied beneath the altar of the chapel. There was also found the body of a small child whose identity thus far remains unknown. The archaeological report precludes the possibility of the child having been buried after the French left in 1758. There was no evidence of a coffin and, unlike the other bodies, which were placed with the head pointing away from the altar, this body was placed roughly parallel to the altar.[14] This was undoubtedly an irregular burial whose secret was lost with the fall of the city. ...

[ENDNOTES]

CHAPEL

1. Toisé des ouvrages, 4 May 1727, AN. Col., C11B, vol. 9, ff. 214,219v,223,226,228,229.

2 Supplement de Marché, 12 November 1726, AN. Col., C11B, vol. 8, ff. 167-67v.

3. Verrier to Minister, 10 October 1726, AN. Col., C11B, vol. 8, f. 112.

4. Procès contre Le Bon, 25 October 1754, AN. Section Outre-mer, G2 vol. 189, f. 264.

5 Acte de réquisition, 18 October 1726, AN. Section . Outre-mer, G3, vol. 2058, no. 36.

6. Registres Paroisialles, 11 May 1740, AN. Section Outre mer, G1 , vol. 407, registre I.

7 Registres Paroisialle, 19 September, 17 November, 2 December, 17 December 1735, AN. Section Outre-mer, G1, vol 406, registre IV.

8. Bourville et Le Normant to Minister, 21 October 1738, AN. Col., C11B, vol. 20, f. 54. Memoire concernant les missionnaites par De Raymond, January 1752, SHA. A1, vol. 3393, f. 38.

9. Etat des frais de justice a l'occassion de la succession de feu M. Decouagne, 1740, AN. Section Outre-mer, G2, vol. 197, Dossier 129, No.13.

10. De Mesy to Minister, 3 February 1732, AN. Col., C11B, vol. 13, ff. 11-13.

...

14. Archaeological Report on the King's Chapel, Vogel,1965, p.24 & 27.(unpublished in Louisbourg archives).

Brenda, Dunn. Block 2, Lot G, Property of the Commissaire. Unpublished report H D 14 R (Fortress of Louisbourg, 1969) [For the complete report, click on the title]

HOUSE OF THE COMMISSAIRE ORDONNATEUR

FIRST PHASE

I. HOUSE OF THE COMMISSAIRE ORDONNATEUR

A. First Phase 1721-1735

1. Chronology

Lot

G had been conceded to Genier in 1717. [1] The concession ran 30 pieds

along the Quay and 108 pieds into the Block, bounded on the east side by

a property reserved for the King, and on the west by a property belonging to

Rodrigue. M. de Mesy purchased the property in 1720 for 800 livres. [6a]

...

Everything being in order, deMesy began to pour the foundations of his house in

the spring

of 1721. [3b] ...

M. deMesy suspended work on his dwelling during the winter of 1721 ... [7a]

________

[ENDNOTES]

1 A.N., Colonies, C11B, Vol 2, fols. 151-61, Toises des Graves et Concessions accordées par Messieurs de Costebelle et Soubras aux habitans de Louisbourg, 13 novembre 1717.

...

3b Ibid. [A.N., Outre Mer, G2, Vol. 178, fols. 244-51, Contestations d'Entre Mr. de Mesy et Le Sr. Rodrigue a Loccasion de Leur Emplacemen, 15 juin 1721.]

...

6a Ibid., C11C, Vol. 15 suite, pièce 206, Conseil a Mr. de Mezy, 17 mars 1722 [24 novembre 1721].

...

7a Ibid., pièce 211, Conseil à M. de Mezy, 24 mars 1722 [7 décembre 1721].

...

II.

MAGASINS OF THE COMMISSAIRE ORDONNATEUR

A. Chronology

M. deMesy began constructing a magasin on lot G in 1720. (See plans

720-2and 720-4.) It was situated, in alignment, along the Rue St.

Louis boundary. By June of 1721, the building had been completed ...

[3...] ...

In 1721-1722, the Council questioned the purpose for which the building

was intended and the source of materials used in its construction. [4,6a]

The Curé accused deMesy's labourers of taking stones from the church's

property, probably the adjacent lot on the northwest corner of Block 3.

... [6] ...

________

...

3a A.N., Outre Mer, G2, Vol. 178, fols. 244-51, Contestations d'Entre Mr. de Mesy et Le Sr. Rodrigue a Loccasion de Leur Emplacemen, 15 juin 1721.

...

4 A.N., Colonies, B. Vol. 44-2, fols. 570v.-73, Conseil a Demesi, 6 juillet 1721.

...

6a Ibid., C11C, Vol. 15 suite, pièce 206, Conseil a Mr. de Mezy, 17 mars 1722 [24 novembre 1721].

....

Hoad, Lynda. Report On Lots A AND B Of Block 3. Unpublished Report H D 16 (Fortress of Louisbourg, June 1971) [For the complete report, click on the title]

PART

I

LOTS A AND B

1713 - 1723

...

[PAGE 2:]

A) THE RECOLLET CHURCH

The

Recollet's building, including the Church and some "adjoining"

storehouses (see plans 1717-2 and 1718-2), belonged to the king, but

improvements had been made to the Church and the lodging by the Recollet fathers

[NOTE 2]. According to the inventory and estimation, the parish church was at

one end of the building, which was built of pickets 93 pieds long and 20 pieds

wide. The roof was covered partly in planks, and partly in bark. There was at

least one fireplace in the building; the Recollets repaired sashes, doors and

the foundations, and supplied window panes, hardware, and nails [NOTE 3].

Although the building is not marked with a cross after 1718, it is shown on all

the plans until 1724, and is indicated on plan 1723-2 as "the old church

where divine service is presently held" [NOTE 4]. It is not known when the

building ceased to function as a church, but is possible that more details will

become available when the research for the rest of the block is completed. The

building must have been destroyed or removed before 1726, since plan 1726-4

shows Beauséjour's house on the site of the old church.

There was a cemetery in Block 3 at this period. Although it is not shown on the

plans, it must have been either in the area shown as a garden on plans 1717-2

and 1718-2, or, more likely, in the area south of the garden. LaCombe's house

was bounded by the cemetery, and both Lagrange and Beauséjour complained that

there were burials on their concessions. (see infra, pp. 8 &, 19)

...

[ENDNOTES]

PART

I:

[NOTE 1:] 30 septembre 1715, AC C11B, Vol. 1, ff. 257-58. St-Ovide et L'hermitte

"Inventaire des maisons faites en l'année 1713 dans le havre de Louisbourg

de ce qui a Esté fait par les ouvriers du Roy Et fournitures"; 19 octobre

1715, AC C11B, Vol. 1, ff. 255-56. "Estimation faite par les S. Lelarge et

Morin des Maisons du Roy qui sont au sud du Port de Louisbourg dans L'Isle

Royale".

[NOTE 2:] ibid.

[NOTE 3:] ibid.

[NOTE 4:] 1723, AC C11A, Vol. 126, 111, [pp. 237-39]. "Estat des

Emplacements concedés a Louisbourg dans 1'Enceinte de la Place, relatif au plan

de 1723".

...

(D) LAGRANGE PROPERTY

Jean

Lagrange was sent from the hospital in Rochefort in 1713, as chirurgien major

[NOTE 12]. He built a house in Block 3 which served as a hospital during the

winter of 1713-14 [NOTE 13]. This building will be referred to as Lagrange I. He

also built a storehouse in front of the house, near the harbour (Lagrange II), a

garden, and in 1714 another house near the harbour (Lagrange III) [NOTE 14].

In July 1715, DeCouagne surveyed Lagrange's property: it was 60 pieds at

the front, 160 pieds in the middle because of the garden, and 250 pieds

deep, bounded by Genier in Block 2, the sea, and the cemetery. This land,

somewhere in the vicinity of the bakery, was not conceded to Lagrange at this

time [NOTE 15].

In October 1715, Lagrange went to Port Dauphin with the Governor and Ordonnateur

and most of the garrison [NOTE 16]. He left Louis Lachaume, a sergeant, in

charge of his Louisbourg properties, although he also claimed that he was forced

to cede them to the King [NOTE 17].

In 1717, de Verville surveyed the site for the parish church, cloister and

garden for the Recollets. He noted that the site was on a height near the port,

and belonged to Lagrange, who would have to be compensated for the loss [NOTE

18]. The house which Lagrange had built in 1713 (Lagrange I) was in the way, and

it was demolished and the debris burned at the King's bakery in October and

November of 1717 [NOTE 19]. It does not appear on plan 1717-2 and we have no

earlier plans of the area.

[PAGE 7:]

Lagrange I was a picket structure 37 pieds by 20 pieds containing

a chimney and an oven. The floor and sleepers were made of squared pickets and

the roof was of bark [NOTE 20].

Lachaume lived in the second house (Lagrange III) until at least 1719 [NOTE 21].

It had served as a hospital in 1715, and then housed some of the King's

employees. It was described in the inventory and estimation of 1715 as a picket

building with a bark roof, measuring 30 pieds by 20 pieds. Some

work was done on the building when it was converted to a hospital, and the

estimation includes fireplaces, double leaf doors, foundation, sashes, window

panes, hardware, partitions and nails [NOTE 22].

When Lagrange returned to Louisbourg in approximately 1719 [NOTE 23], he found

that the house was almost in ruins, and he had an estimate made in 1720. The

estimate gave the dimensions as 27 pieds by 18 pieds, but the rest

of the details given in this document correspond to those mentioned in 1715. The

house was built of pickets, with picket floors and partitions. It had

originially had braces ("arboutant, ou a corde qui tenoist lade. maison"),

but they had been removed. There had been two windows, one facing the port and

the other facing the land, but only the one facing the land contained a sash by

1720, and only 7 panes of glass remained intact. All the interior doors had been

removed, and of the hardware, only a part of the latch and a nail remained on

the main door. The roof was covered with "plans de terre et de bois"

[NOTE 24]. The house must have looked very much like the Lartigue buildings in

Block 1, shown on plan 1731-3.

[PAGE 8:]

The only information found concerning the storehouse (Lagrange II) is in an

estimation of Lagrange's property made in 1717. It was built of pickets, 40 pieds

long and 30 pieds [Sic: 20] wide, resting on picket sleepers. The roof was of bark

[NOTE 25].

These two buildings are shown consistently until 1720, the larger one presumably

being the storehouse. Neither of them are shown on plan 1722-1, but they appear

again on plan 1723-2 (marked C), and on plan 1723-4. Neither are shown on plan

1724-2; thus they must have been removed between 1723 and 1724.

In August 1720,

Lagrange received a concession for a property 96 pieds along the

Rue de l'église and 56 pieds along the Rue du Cloître, bounded on

the east by Depensens [NOTE 26]. By 1722, he was again threatened with

confiscation, this time for the parish church and the quay. He stated that

he had built a house on his new concession (Lagrange IV), and that the

land being offered as recompense for moving was situated in the old

cemetery in Block 3. He pleaded a numerous family, including the first

male child born in the colony, as reasons for special consideration, and

requested that he be allowed to remain in possession of his latest

concession [NOTE 27].

In 1723, he finally received a concession for Lot A: 56 pieds along

the quay and 105 pieds along the place de l'église (Property "C" on

plan 1723-2). This concession was confirmed and registered by the Conseil

Supérieur in 1735, and Lagrange appears to have suffered no further

difficulties [NOTE 28].

[PAGE 9:]

There is no information concerning Lagrange IV. It is shown first on plan

1720-2, omitted on 1720-4, but appears again on plan ND 6. It is not shown

on 1722-1, but is shown again on plan 1723-2, in a more northerly

location. Plans 1723-3, 1723-4, and 1724-2 also show the building in this

position. It seems to have been replaced by another larger building by

1726, but there is an outbuilding shown on many of the later plans - which

may be this earlier building. (see infra p. 12 & 13). Thus, the

house was probably built about 1720, and destroyed or moved before 1726.

[ENDNOTES]

... [NOTE

12:] 20 avril 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15, pièce 113. Conseil de Marine.

[NOTE 13:] 27 janvier 1717, AC C11C, Vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat de

L'hermitte, joint à la lettre du Sr Lagrange au Comte de Toulouse; 22 juillet

1719, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Lettre de L'hermitte au Sieur

Lagrange.

[NOTE 14:] 18 février 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

"Estimation des maisons que Le Sr. Lagrange a fait faire au havre de

Louisbourg ... "; 27 octobre 1722 AC C11C vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. "Etat

des pretentions du Sr. Jean Lagrange Chirurgien a Louisbourg ... ".

[NOTE 15:] 17 juillet 1715, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat de

DeCouagne.

[NOTE 16:] 26 février 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15, pièce 77. Conseil de Marine.

[NOTE 17:] 23 novembre 1719, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat du

Sieur Lachaume; 21 novembre 1719, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

Certifficat de Laforest.

[NOTE 18:] 19 fèvrier 1717, AC C11C vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat du

Sieur de Verville.

[NOTE

19:] 21 novembre 1719, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat de

Laforest.

[PAGE iii]

[NOTE 20:] 18 février 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

"Estimation des maisons que LeSr. Lagrange a fait faire au havre de

Louisbourg."

[NOTE 21:] 21 novembre 1719, AC C11 C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Certifficat de

Laforest.

[NOTE 22:] 30 septembre 1715, AC C11B, vol. 1 ff. 257-58; 19 octobre 1715, AC

11B, vol. 1, ff. 255-56.

[NOTE 23:] 12 avril 1717, AC B, vol. 39-5, p. 986. Conseil de Marine à

Costebelle et Soubras; 20 avril 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15, pièce 113. Conseil de

Marine; 20 novembre 1719, AFO G3, carton 2056, no. 35. Rapport de visite de

cadavre.

[NOTE 24:] 23 août 1720, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. "Memoire de

Letat ou Se trouve La maison quoqupoit Sy devante LeSr. Lachaune appartenant au

Sr. Lagrange".

[NOTE 25:] 18 février 1717, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

"Estimation des maisons que LeSr. Lagrange a fait faire ...".

[NOTE 26:] 22 août 1720, AFO Gl, Vol. 466, pièce 83, f. 4. "Louisbourg

Conseil Superieur Concessions".

[NOTE 27:] 28 octobre 1722, AC C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. Lettre du

Sieur Lagrange au Comte de Toulouse; 27 octobre 1722, AC C"C, vol. 15

suite, pièce 230. "Etat des pretentions ... ".

[NOTE 28:] 15 septembre 1735, AFO Gl, vol. 466, [pièce 85], f. 7. "Ratiffication

faitte par Sa Majesté des Concessions des habitans de Louisbourg".

....

PART III

LOT A

1723-1768 ...

[PAGE 11] ...

In 1768, the Lagrange house was described as a private residence built of stone and occupied by Keho, a fisherman, and in tolerable condition. There was another building west of the house which served as a Guard House. It was described as a wooden structure, in tolerable condition [NOTE 16]. (see plan 1768-1) ...

[NOTE

16:] September 26, 1768, CO 217, vol. 25, pp. 139-44. "The State of the

Town of Louisbourg, on the 10th of August 1758", enclosed in a letter from

Franklin to Hillsborough

....

LOT B

1723-1768

[PAGE

18]

I. CHRONOLOGY

Lot B was granted to François Cressonet dit Beauséjour prior to the

Ordonnance of 1723, on condition that his buildings in Block 1 be

demolished within three years [NOTE 1]. Beauséjour was one of the earliest

inhabitants of Louisbourg and had settled in Block 1 before that area was

reserved for the king [NOTE 2]. He also owned a lot in Block 2, acquired

in 1723 [NOTE 3]. The actual date of the Block 3 concession is not

certain, and the dimensions vary. According to the registers of the

Conseil Superieur, the concession was dated June 1724 and consisted of 46

pieds along the quay and 102 1/2 pieds along the Rue de

1'étang [NOTE 4]. The final confirmation of concessions based on Vallée's

survey dated the concession as May 31, 1723, and gave the depth as 105

pieds [NOTE 5].

Plan 1723-2 states that the small building E belonged to "Francoeur

Cabaretier, who started to fish this year" [NOTE 6]. One can only assume

that this was an error, since there are no further references to François

Lessenne dit Francoeur in connection with this lot. Moreover, Francoeur

was never, to our knowledge, a cabaretier, and Beauséjour most certainly

was.

[PAGE 19:]

In 1725, the bones found on Beauséjour's property, the site of the early

cemetery, were "solemnly transported" to the new cemetery [NOTE 7]. In the

same year Beauséjour's step-son, Jean Baptiste Guyon, married Anne

Lachaume. Beauséjour and his wife Marguerite Dugas were building a house

in Block 3, and they gave their Block 2 house to Guyon with the provision

that they might continue to live there until the house in Block 3 was

finished [NOTE 8].

...

The first plan to show Beauséjour's house is 1726-4, on which it appears as an L-shaped building, immediately adjoining Lagrange's house.

[ENDNOTES]

PART III

[NOTE 1:] 31 mai 1723, AC C11C, vol. 16, piece 6. "Ordonnance du Roy".

[NOTE 2:] 1717, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 67-78, "Toiséz des graves et

concessions ...".

[NOTE 3:] 18 août 1719, 11 mai 1720, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 133-34, "Extrait

du Registre du greffe du Conseil Superieur de Louisbourg ... "; Brenda

Dunn, Report on Block 2, p.

[NOTE 4:] 1 juin 1727, AFO Gl, vol. 466, pièce 83. ff. 22(v)-23, "Louisbourg

Conseil Superieur Concessions"; 1 juin 1724, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 135-44,

"Extrait du Registre du greffe du Conseil Superieur de Louisbourg ... ".

[NOTE 5:] 15 septembre 1735, AFO Gl, vol. 466, pièce 85], ff. 7-7(v), "Ratiffication

faitte par Sa Majesté des Concessions des habitans de Louisbourg".

[NOTE 6:] 1723, AC 11A, vol. 126, 111, [pp. 237-39], "Estat des

Emplacements concedés a Louisbourg dans 1'Enceinte de La Place, relatif au

plan de 1723".

[NOTE 7:] 24 décembre 1725, AFO G3, Vol. 406, registre III, f. 3, "Décés

1722- 28."

[NOTE 8:] 5 novembre 1725, AFO G3, carton 2058, no. 36, Contrat de mariage.

...

PART III

LOT B

1723 - 1768

[PAGE 18]

I. CHRONOLOGY

Lot B was granted to François Cressonet dit Beauséjour prior to the

Ordonnance of 1723, on condition that his buildings in Block 1 be

demolished within three years [NOTE 1]. Beauséjour was one of the earliest

inhabitants of Louisbourg and had settled in Block 1 before that area was

reserved for the king [NOTE 2]. He also owned a lot in Block 2, acquired

in 1723 [NOTE 3]. The actual date of the Block 3 concession is not

certain, and the dimensions vary. According to the registers of the

Conseil Superieur, the concession was dated June 1724 and consisted of 46

pieds along the quay and 102 1/2 pieds along the Rue de

1'étang [NOTE 4]. The final confirmation of concessions based on Vallée's

survey dated the concession as May 31, 1723, and gave the depth as 105

pieds [NOTE 5].

Plan 1723-2 states that the small building E belonged to "Francoeur

Cabaretier, who started to fish this year" [NOTE 6]. One can only assume

that this was an error, since there are no further references to François

Lessenne dit Francoeur in connection with this lot. Moreover, Francoeur

was never, to our knowledge, a cabaretier, and Beauséjour most certainly

was.

[PAGE 19:]

In 1725, the bones found on Beauséjour's property, the site of the early

cemetery, were "solemnly transported" to the new cemetery [NOTE 7].

....

II. CARTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE (see also Part V)

The first plan to show Beauséjour's house is 1726-4, on which it appears as an L-shaped building, immediately adjoining Lagrange's house ...

ENDNOTES

[PAGE vi:]

PART III:

[NOTE 1:] 31 mai 1723, AC C11C, vol. 16, piece 6. "Ordonnance du Roy".

[NOTE 2:] 1717, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 67-78, "Toiséz des graves et

concessions ...".

[NOTE 3:] 18 août 1719, 11 mai 1720, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 133-34, "Extrait

du Registre du greffe du Conseil Superieur de Louisbourg ... "; Brenda

Dunn, Report on Block 2, p.

[NOTE 4:] 1 juin 1727, AFO Gl, vol. 466, pièce 83. ff. 22(v)-23, "Louisbourg

Conseil Superieur Concessions"; 1 juin 1724, AFO Gl, vol. 462, ff. 135-44,

"Extrait du Registre du greffe du Conseil Superieur de Louisbourg ... ".

[NOTE 5:] 15 septembre 1735, AFO Gl, vol. 466, pièce 85], ff. 7-7(v), "Ratiffication

faitte par Sa Majesté des Concessions des habitans de Louisbourg".

[NOTE 6:] 1723, AC 11A, vol. 126, 111, [pp. 237-39], "Estat des

Emplacements concedés a Louisbourg dans 1'Enceinte de La Place, relatif au

plan de 1723".

[NOTE 7:] 24 décembre 1725, AFO G3, Vol. 406, registre III, f. 3, "Décés

1722- 28."

...

Hoad, Linda , Surgery and Surgeons in Ile Royale. Unpublished Report H F 21 (Fortress of Louisbourg, September, 1972) [For the complete report, click on the title]

PART TWO:

Jean Baptiste LaGrange

LAGRANGE AS SURGEON MAJOR

Nothing is known about Jean Baptiste Martin Lagrange prior to his arrival in Louisbourg in 1713 ...

...

in the meantime, Lagrange went with de Costebelle and Soubras to Port Dauphin in October of 1715 when it was decided to make that port the principal establishment on the island. [172] ...By October 1716, the Brothers had arrived in Port Dauphin, and Lagrange found himself without a job. He and his family were "reduced to the last extremity" and Lagrange returned to France on the Atlante, arriving at the Ile of Aix on December 28, 1716. [176] ...

Lagrange's first step towards rehabilitation was a request to the Council of Marine for the position of surgeon major at Louisbourg, the salary and rations owed to him, and compensation for his property losses. [182] The first part of this request could not be granted because Le Roux had already been appointed. The Council calculated that Lagrange was owed 1233 livres 6 sols 8 deniers in unpaid salary. [183] His property losses were valued at 1200 livres, and the Council suggested that he also be given the choice of another concession to replace the one he had lost in Louisbourg. This claim was not finally settled until 1724.

Not content with this reaction to his misfortunes, Lagrange submitted a second list of requests two months later for a concession on the waterfront at Louisbourg, title to his Port Dauphin property so that he could sell it, permission to practice surgery in Ile Royale, the position of cadet for his 12 year old son, payment for shaving the troops and officers for three years and 8 months and free passage to Ile Royale. [184] The Council encouraged him to return to Ile Royale by giving him free passage (including 4 engagés and 2 tonneaux of provisions, and permission to practice surgery, but made no comment about his other requests. [185] Lagrange seems to have contented himself with this for the time being.

It is not known when Lagrange returned to Ile Royale, but it may have been as early as 1717. He stated that he was forced to abandon his property in Port Dauphin in 1717 and set up a practice in Louisbourg "in order to support his family". [186] He was in Louisbourg by September 1718, when he examined the corpse of a fisherman. [187] However, he was listed in the census of 1719 as a resident of Port Dauphin, [188] although he described himself in November of that year as "former surgeon major for the king, at present master surgeon established at Louisbourg". [189] He was listed in the 1720 census as a resident of Louisbourg, [190] and was granted a concession in August or September of that year for property in Block 3. [191]

In October 1722, Lagrange made another plea for compensation for his property losses. These losses totalled 5700 livres and his claims were supported by certificates signed by L'Hermitte, de Verville, Soubras, de Couagne and de la Forest. [192] ...

LAGRANGE AS MERCHANT

Although Lagrange is referred to only once in the available documentation as a merchant, there are numerous indications that he was engaged in some kind (or several kinds) of commercial activity. The only direct reference occurs in the 1720 concession for lot A in Block 3 where he is described as a "Mar[chan]d M[aitr]e chirurgien". [215]

Lagrange seems to have begun his commercial activities as soon as he arrived. In 1713 he built a house, and a storehouse which measured 40 pieds by 20 pieds, then another house in 1714. [216] The probable use of the storehouse is revealed in the 1715 census: besides his family, an apprentice and a valet, Lagrange's establishment consisted of two fishermen. [217] When Lagrange left for Port Dauphin in 1715: he left his Louisbourg properties (and possibly his business enterprise?) in the hands of Louis LaChaume, a retired sergeant. [218]

Nothing is known about Lagrange's activities in Port Dauphin, except that he built two houses with courtyards and gardens there which he was forced to abandon in 1717 and which were reported to be in ruins in 1722. [219] He spoke of selling this property in 1717, [220] but it appears that he did not do so before 1722. There is no reference to the Port Dauphin property in the "Statement of the widow Lagrange's losses", so it must have been sold or abandoned after 1722. [221] ...

However, most of his energy seems to have been expended in getting compensation for his property losses, and in acquiring more property. His original concession in Louisbourg had been diminished because part of it occupied the site reserved for the parish church. One of his houses had been demolished, and the other one was in ruins. In 1720 he received a concession for the property in Block 3 where he seems to have established himself again, as he noted, for the sixth time. [225] Lagrange seems to have been determined to remain in the area of his first concession; it is significant that in 1717 he asked for a concession on the waterfront, and was eventually allowed to stay there, although officially the waterfront concessions were reserved for merchants. [226] ...

Lagrange seems to have had a passion for owning property; he built two houses and a storehouse in Louisbourg, and two more houses in Port Dauphin. He apparently did not speculate with these properties, so it must be assumed that he acquired them for the purpose of developing them and collecting the rents. Without more information about his commercial dealings however, it is impossible to estimate their success or the amount they contributed to his income. ...

[ENDNOTES]

...

172 Conseil de Marine, 26 février 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15, Pièce 77.

...

176 Conseil de Marine, 26 février 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol, 15 pièce 77.

...

182 Conseil de Marine, 26 février 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15, pièce 77. These losses included two houses and a storehouse at Louisbourg and two houses at Port Dauphin. See the next section, and also L. Hoad, Report on Lots A and B of Block 3. (Unpublished manuscript, Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, 1971).

183 Ibid. Three separate payments totalling 800 livres were made to Lagrange in March 1717; "De par le Roy". Paris, 15 mars 1717, AN Colonies, F1A, vol. 19, ff. 232, 233, 234. No further references have been found to this claim for compensation.

184 Conseil de Marine, 9 avril 1717, AN Colonies, C11C. vol. 15, pièce 90.

185 Conseil de Marine, 20 avril 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15, pièce 113; ibid., Conseil à De Costebelle et Soubras, Paris, 12 avril 1717; AN Colonies, B, vol. 39, f, 264.

186 "Etat des pretentions du Sr. Jean Lagrange Chirurgien a Louisbourg ...", Louisbourg, 27 octobre 1722, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

187 "Proces criminel ... contre les Nommées gilles carbonnet et Jean Samson ...", Louisbourg, 15 septembre 1718, AN Section outre-mer, G2, vol. 178, ff. 101-194.

188 "Estat du nombre des familles ...", Ile Royale, 1719, AN Section outre-mer, G1. vol. 466, pièce 60.

189 Raport de visite de cadavre, Louisbourg, 20 novembre 1719, AN Section outre-mer, G3, carton 2056, no. 35.

190 "Ressencement des habitants residants ...", Ile Royale, 1720, AM Section outre-mer, G1, vol. 466, pièce 62.

191 Concession d'un terrain, Louisbourg, 22 août 1720, AN Section outre-mer, G1, vol. 462, ff. 133-134; 20 septembre 1720, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

192 Lagrange au Comte de Toulouse, Louisbourg, 21 octobre 1722, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. This request must have been preceded by others because in March the Council had already decided to award him 1500 livres of the 4300 livres he had requested. Conseil de Marine, 24 mars 1722, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 210.-

...

215 "Extrait du Registre du greffe du Conseil Superieur ... pour les concessions ...", Louisbourg, 22 août 1720, AN Section outre-mer, G1, vol. 462, ff. 133-134.

216 "Etat des pretentions du Sr. Jean Lagrange Chirurgien a Louisbourg ...", Louisbourg, 27 octobre 1722, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230. See also Hoad, Export on Lots A and B of Block 3. Unpublished Manuscript, Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, 1971.

217 "Recensement des habitants Etablis dans le havre de Louisbourg ...", Louisbourg, 4 janvier 1715, AN Section outre-mer, G1, vol. 466, pièce 51.

218 Certificat de Sieur LaChaume, Louisbourg, 23 novembre 1719, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

219 "Etat des pretentions du Sr. Jean Lagrange ...", Louisbourg, 27 octobre 1722, Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite, pièce 230.

220 Conseil de Marine, 9 avril 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15, pièce 90.

221 "Etat des pertes que la veuve de feu la Grange ... a Faites par laprise de ladite Isle ...", [Bayonne], s.d., AN Colonies, E. 227, dossier Imbert et Lannelongue, pièce 8.

...

225 Ibid. [Lagrange au Comte de Toulouse, Louisbourg, 21 octobre 1722, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15 suite pièce 230. ]; "Extrait du Registre ...", Louisbourg, 22 août 1720, AN Section outre-mer, G1. vol. 462, ff. 133-134.

226 Conseil de Marine, 9 avril 1717, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 15, pièce 90; "Ordonnance du Roy", 31 mai 1723, AN Colonies, C11C, vol. 16, pièce 6 pièce 6 and Brenda Dunn, Block 2, Unpublished Manuscript, Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, 1971, p. 9.

...

(i) The Récollets de Bretagne

The spiritual welfare of the people of Louisbourg was in the hands of Récollet friars. From the date of the town's founding in 1713 to its final fall in 1758, Récollets served the Louisbourg community as curds (parish priests) and chaplains. In both capacities their goal was the same: to direct the behaviour and consciences of their charges so as to lead them toward morally acceptable behaviour in this world and salvation in the next.

During the 1740s there were normally four Récollets in Louisbourg, a curé and three chaplains (one each for the troops in the barracks, for the sick in the hospital and for the detachment posted to the - Royal Battery) ...

... [...30...] 2. Curés and Chaplains: The Récollets of Brittany ...

The spiritual welfare of the people of Louisbourg was in the hands of Récollet friars. From the date of the town's founding in 1713 to its ultimate fall in 1758, Récollets served Louisbourg's civil and military populations as their curés and chaplains ...

[...34...] ... One of the factors motivating people to sign the petition in support of the Récollets was the understandable desire to have a church to attend. The only church or chapel in the town in 1718 was located in part of a large building (93 pieds by 20 pieds) close to the waterfront. Though the structure had been erected in 1713 with royal funds, by 1718 the Récollets appear to have assumed ownership, at least in the eyes of the inhabitants, who feared that if the parish were handed over to secular priests the friars would no longer allow the chapel to be used as the town's church.

It was probably partly in response to that concern, as well as out of a simple desire to have a major church edifice in the town, that the first official proposal to build a new church was made. In 1720 Commissaire ordonnateur Jacques-Ange Le Normant de Mézy submitted the project to the Conseil de Marine for consideration.[12] By way of introduction to the subject Mézy put forth the view that colonists were unlike the typical citizens of France. They did not feel attached to the settlements where they lived; rather, they came to colonies out of "avarice" and while there "they think only of their own personal interests." The commissaire-ordonnateur disapproved of such self-interest and argued that the construction of public edifices, such as a parish church, might help to settle the colonists in their communities and foster sentiments of pride and belonging.

To illustrate his point Mézy described the situation in Louisbourg concerning the need for a place to worship. He claimed that there was hardly a stable in France that was not "more beautiful and more clean" than the structure currently used as a church. On a number of occasions he and Governor Saint-Ovide had assembled the inhabitants in the hope of convincing them to contribute toward the construction of a new parish church and presbytery. But, according to Mézy, the parishioners "promise much but give little." The Récollets blamed the churchwardens (marguilliers) for the lack of public interest in the project and the churchwardens stated that it was useless to collect for a new church since the friars would send the money to France for their convents there. The commissaire ordonnateur added that there seemed to have been some truth in the latter complaints. It was said, by Governor Saint-Ovide and several of the principal residents of the town, that the Récollets "have always carried away considerable sums," with the figure for 1720 reaching 4,000 livres.

Convinced that the colonists would never construct a church at Louisbourg on their own initiative, Mézy urged the Conseil de Marine to reimpose a compulsory tax on the fishing industry. In 1715 a tax of a [...35...] quintal (48.95 kilograms) of cod per shallop had been collected with an eye to offsetting hospital costs on Ile Royale. Though such a tax had been collected at Plaisance, the merchants and fishermen of Louisbourg protested until the tax was lifted in 1716. The commissaire-ordonnateur maintained that the time had come to reimpose the tax to pay for the public edifices the town needed. In addition, he hoped that skilled tradesmen (masons and carpenters) might be sent to the colony to erect the required structures.

While Mézy was awaiting the official response to his suggestions, the chief engineer at Louisbourg, Jean-François de Verville, apparently decided to begin work on the project. In December 1721 the governor and commissaire-ordonnateur reported that Verville had laid a portion of the foundation for the proposed church and presbytery in the lots on Block 3 set aside for those structures.[13] But the construction was stopped by Saint Ovide and Mézy when the Récollets sought to place a copper plaque in the foundation that made mention of their order. The royal officials interpreted the action as an attempt by the friars to appropriate the church and rectorship of Louisbourg to their order in perpetuity. Worried that the king would not remain the patron of the new church, and thus have control over naming who would serve the parish, Saint-Ovide and Mézy had felt obliged to stop all work on the structure. They urged Versailles to provide the funds to build at least the chancel (choeur). They argued that the cost would be relatively small, but the control thereby gained by the king would be essential. As for the copper plaque, it was withdrawn and two medals (one bronze, one silver) bearing the profile of Louis XV on one side and a conjectural view of Louisbourg on the other were placed in the foundations in its place. [14]

The officials in France agreed that it was desirable to have a new parish church and presbytery in Louisbourg, yet they did not attach the same importance to it that Mézy did. They decided to reintroduce the annual tax on the fishery in 1722, as had been recommended by the commissaire-ordonnateur in 1720. Initially, however, the proceeds were to go exclusively towards the construction of the Hôpital du Roi. Only after the hospital was completed was the revenue to be used for a church and priest's residence.[15]

Anyone who was hopeful of having a parish church eventually erected at Louisbourg through the collection of the tithe (dîme) on the fishery was soon disappointed. Protests over the tax surfaced quickly, as had happened in 1715, and in 1723 the tithe was discontinued for the second and final time.[16]

With the project for funding the construction of a parish church set aside, attention seems to have shifted to the adjacent land on Block 3 which had been granted to the Récollets of Brittany in 1717. During the [...36...] early 1720s a residence and chapel belonging to the friars were brought to completion on this property (Lot C). Possibly the structure which became the residence was built upon the presbytery foundation which Verville had laid in 1721. Similarly, the tax money (a total of 1,700 livres 13 sols) which had been collected during 1722 and 1723 may also have been used to help pay for the Récollet buildings, since permission had been given to use the funds on construction of a parish church.[17]

While the Récollet chapel was being built, the old church on the waterfront continued to be used. In 1723, and probably in early 1724, religious services were still being held there.[18] Those services were likely shifted to the new chapel during the spring of 1724. The first indication of the chapel, the Chapelle de Sainte-Claire, being used as the town's parish church appears on a parish record entry for 12 April 1724.[19] The building on the waterfront which had housed Louisbourg's first church was removed sometime between 1724 and 1726 to make way for a private dwelling.[20]

The Récollet chapel served as the Louisbourg parish church for roughly a decade. Then, in the mid-1730s, the parish church function was transferred from there to the barracks or garrison chapel, the Chapelle de Saint-Louis. The change was apparently made following a request by the friars.[21] Whether the Récollet chapel had suffered from its decade of continued use by hundreds of parishioners or whether the religieux simply found it too inconvenient and inappropriate to have a parish church in a small chapel is not known.

Around the time that parish church functions were moved the question of the need for a permanent full-sized church came to the fore again. On this occasion the issue was raised by a secular priest, Jean Lyon de Saint-Ferréol, curé of Québec at the time, who visited Louisbourg in the fall of 1735 on his way to France. In a subsequent report, which was to be forwarded to the minister of marine, Lyon recommended several measures which he considered necessary to improve the quality of religious life on Ile Royale.[22] First and foremost he urged that a parish church be built with royal funds. In marshalling his arguments for such an undertaking, Lyon reiterated most of the points which had been made by others before him. To begin with, he stated that the inhabitants could not afford to build a large church by themselves. Since the garrison chapel served as the parish church at the time, the residents were showing neither interest in contributing to its upkeep nor in paying customary church charges, nor even in electing churchwardens. They left all financial and maintenance responsibilities to the Récollets and to royal officials in the town. Perhaps the most important drawback of using the Chapelle de Saint-Louis as the parish church was that it was too small to accommodate large numbers of [...37...] parishioners. The visiting vicar-general found the situation deplorable and urged that a new church be built by the king, using funds from the fortifications allotment. Lyon's expectation was that if a sum of money from the royal treasury was committed to the project, the inhabitants would willingly contribute. Without a royal commitment, he correctly foresaw that the people would do nothing.

The commitment which Lyon de Saint-Ferréol argued for was not forthcoming. In January 1737 the minister of marine explained to the Récollet provincial that the current situation simply did not permit the king to undertake any new expenditures. Three months later the minister mentioned to the governor and commissaire-ordonnateur the possibility of additional funds for a church, but first he requested that they send him a plan, a cost estimate, and an indication of what the inhabitants could contribute. The chief engineer at Louisbourg, Etienne Verrier, produced the requested plan and estimate during 1737 and in January 1738 they were forwarded for the minister's consideration. The commissaire-ordonnateur, Le Normant, wrote that the cost could be reduced if the inhabitants contributed materials and labour to the project, but he advised against that approach. In his opinion the structure would be superior if constructed entirely by a hired entrepreneur. [23]

The projected cost (10,200 livres from the inhabitants; 11,780 livres from the king) of a parish church for Louisbourg was apparently more than the officials in France were willing to consider. In the spring of 1738 the minister notified the governor and commissaire-ordonnateur that it was not yet the appropriate time to erect a large church. The fortifications of the town would have to be completed first. The local officials duly informed the residents of Louisbourg of that decision, but they may have held out the possibility that at some point in the future a church might be built.

It was with that goal in mind that the governor and commissaire-ordonnateur again pointed out to the minister that a new church was "absolutely necessary because of the size of the Louisbourg population and the fact that the barracks chapel is too small and inconvenient."[24]

Notwithstanding any promises or hopes expressed in the 1730s, Louisbourg was never to have the proposed parish church. The project came up for discussion from time to time but it was always dropped because of the reluctance to act of either the royal officials or the local residents. As Abbé de I'Isle-Dieu, the bishop's vicar-general in France, commented in 1756, circumstances were just not right at Louisbourg for the construction of a parish church and presbytery, "neither on the part of the court who would not contribute to it, nor on the part of the residents, who are more preoccupied with their positions than with the building of a church."[25]

[... 38 ...] The criticism that the inhabitants of Louisbourg were unwilling to contribute toward the construction of a church, that they refused to look beyond their own self-interest, was by 1756 a familiar complaint. And to a degree perhaps, an accurate assessment. What other town of its size, with a combined civilian and military population by the 1740s and early 1750s of from 2,000 to 4,000 permanent residents, was without a parish church? [26] Residents in neighbouring settlements one-tenth the size of Louisbourg, like La Baleine and Lorembec, succeeded in building their own churches by deciding among themselves what each person would contribute to the project.[27] A similar approach could easily have been adopted in the capital of Ile Royale, which had both a larger and a wealthier population. Bishop Dosquet's estimate that the parishioners of Louisbourg could annually donate 5,000 to 6,000 livres to the church [28] may have been high, but it nonetheless suggests that the citizens were probably capable of paying for the construction of a parish church, had they been so inclined.

The reasons why the Louisbourgeois did not undertake the building of a church are unclear. Contemporary critics always spoke of a lack of community spirit or of a tendency toward parsimony, though it is difficult to see why such qualities would have had a stronger hold on the Louisbourg populace than on that of other towns. A more likely explanation is one which takes into account the distinctive situation at Louisbourg. Louisbourg's economy was based principally on private ventures in the cod fishery and merchant trade,[29] yet the most significant buildings and features in the town were those built at royal expense - the fortifications, the barracks, the hospital, the Magasin du Roi, the official residences, the town gates, the quay wall, the sea batteries, and the lighthouse. With so many public structures and edifices having been erected out of royal funds, perhaps the inhabitants came to feel that the king should build them a church as well. Indeed, that very approach was suggested on a number of occasions, both by local officials and visiting religious officials. As it turned out the king and his ministers did not commit the required funds, but they never ruled out the possibility that they might do so in the future. Apparently encouraged by that prospect, the citizens of Louisbourg made no noticeable effort after 1721 to build their own church.

To return to 1724, when the Récollet chapel became the community church, the curé of Louisbourg was then a friar named Claude Sanquer. As was frequently the case for Louisbourg's parish priests, Sanquer was also the superior of the town's Récollet mission, commissaire of all the other Brittany friars in the colony, and a vicar-general of the bishop of Québec.[30] Towards the end of the summer of 1724, Bénin Le Dorz, a friar recently arrived from France, assumed Sanquer's duties as curé, superior, and vicar-general.[31] ...

[...40...] ... The minister, the comte de Maurepas, received letter after letter during the fall and winter of 1726-7 from those concerned on either side. The basic argument of those opposed to the Récollets was that the Louisbourg parish was being poorly served by the friars and that the introduction of secular priests would be a great improvement. Bishop Saint-Vanier, who contended that except for Gratien Raoul all the Brittany Récollets sent to the colony were "reprehensibles," was the strongest proponent of that view.[45] But it was a perspective shared by the commissaire-ordonnateur of Ile Royale. To the standard criticism of the laxness of the Récollets, Mézy added the charge that the friars' first concern seemed to be to collect money in Louisbourg for their convents in France. The figure alleged to have already left the colony was 6,000 livres. [46]...

[...43...] ... Until Caradec arrived in Louisbourg there had never been a vestry (fabrique) established in the parish to take care of church revenue and maintenance. Indeed, before 1721 there do not appear to have been any churchwardens (marguilliers) in the town. Commissaire-ordonnateur Mézy, in December 1720, seems to have been the first person to propose that churchwardens be selected, and his suggestion came seven years after the founding of the town. Mézy believed that two would be sufficient, each of whom was to serve a two-year term. The positions were nonpaying but the commissaire-ordonnateur expected that the two men would be suitably compensated in terms of honour and status. He envisioned them being accorded a prominent pew in the parish church, as was customary in France, and being given seats on the Conseil Supérieur. The first churchwardens were probably chosen by parishioners in March 1721, acting upon Mézy's suggestion. [64] How long marguilliers continued to be selected in the parish is unknown; there seem to have been none in the town by 1742.[65]

The fact that it had apparently taken action by the financial administrator of the colony to bring about the selection of Louisbourg's first churchwardens suggests a certain lack of interest in parish affairs on the part of the residents of the town. The situation obviously improved little in the decade that followed, as demonstrated by the lack of a formal vestry in the community at the time of Zacharie Caradec's inspection of the parish in 1730. The inhabitants explained their attitude to Caradec by [...44...] pointing out that the town did not have its own parish church, but used the Récollet chapel on Block 3 as a substitute. Without their own parish church, they saw no need for a vestry. They simply left the collection of revenue and upkeep entirely to the friars. Caradec disapproved of the irregular situation and set out to rectify it on his terms. He called for the election of three additional churchwardens, there being only one at the time, to look after the business of the parish. To reward the churchwardens for their service to the community, Caradec decided that each one would hold a pole supporting the dais carried in religious processions[66] That decision, combined with a related effort to increase church revenue, soon gave birth to a hotly debated controversy with Zacharie Caradec right at the centre.

The dispute began when visiting ship captains learned that in Louisbourg's religious processions the churchwardens were henceforth to carry all four poles of the dais. Up until that time it had been the practice, first at Plaisance and then at Louisbourg, that two of the poles were held by ship captains. Since this was an age and a society in which customs and privileges were guarded extremely carefully, the break with tradition deeply upset the captains. Their irritation grew when Caradec proposed that all visiting fishing crews be taxed at the rate of 40 sols per man. They protested in the most effective way they could, by ceasing to pay the traditional tithe (dîme) of a quintal [48.95 kilograms) of cod per shallop.

By 1730 payment of the tithe on lle Royale was customary yet nonetheless voluntary. In 1715 and 1722 attempts had been made to collect the tax on a compulsory basis, but each time the measure had been greeted with protest and then lifted.[67] The residents had not objected to the uses to which the money would be put (initially it was to help offset hospital and health care and later it was to pay for the construction of a parish church and presbytery). Rather, they complained that the colony was still in its infancy and they were not yet able to pay a compulsory tithe. A similar argument had been used in seventeenth-century Canada to have the tithe there, which was compulsory, lowered from one-thirteenth, the common rate in France, to one-twenty-sixth of one's income.[68]

During precisely the same period that Zacharie Caradec was attempting to reorganize the Louisbourg parish and to generate additional revenue for the church on Ile Royale, Pierre-Hermann Dosquet, first as coadjutor and then as bishop of Québec, was seeking to convince the minister of marine to restore the tithe in Canada to the rate of one -thirteenth. [69] Conceivably, the actions of the two men may have been related. Caradec was Dosquet's vicar-general and some of the Récollet's innovations at Louisbourg may well have been suggested, or at least supported, by his ecclesiastical superior. Dosquet's efforts, like those of Caradec, were ultimately doomed to [...45...] failure, and for basically the same reason: neither Canada nor Ile Royale was judged by the minister to be sufficiently developed to justify increasing the financial burden on their colonists.

When the ship captains and fishermen who visited Louisbourg seasonally arrived in port, they refused to pay the customary tithe, both because of the change in the town's religious processions and the proposal to tax each crew at 40 sols per man. Their refusal infuriated Zacharie Caradec. He responded by insisting that a few individuals be imprisoned. The situation was exacerbated and the governor and commissaire-ordonnateur found themselves unable to handle the growing strife. Consequently, they sought the intervention of the minister of marine.[70]

The minister ruled that the payment of the tithe was simply a traditional donation, not a tax that could be enforced. Therefore the clergy could use only "the voice of exhortation" to encourage contributions to the parish,[71] a highly unlikely prospect given the animosity which existed between the two sides. He further directed the colonial officials to find some way to conciliate the factions and bring the conflict to an end. Interestingly enough, the initial reports of the dispute did not affect the comte de Maurepas' confidence in Caradec. Indeed, in 1731 he interceded with the provincial of the Récollets of Brittany so that Caradec would not be replaced on Ile Royale as planned. In the minister's opinion, Zacharie Caradec "has reestablished order and discipline among the Religious."[72]

Caradec attempted to deflect criticism over the tithe question from himself by denying that he had ever suggested that visiting ship captains should be forced to pay it. He explained that it was the permanent residents of Louisbourg who rented beach properties, flakes, and fishing boats to visiting crews whom he wanted to see contribute to their parish. [73]Unfortunately for Caradec, here again such compulsion had no legal justification.[74]

It is worth noting that Governor Saint-Ovide sympathized with Caradec in his struggle to increase church revenue. In 1731 the governor observed that Ile Royale was perhaps the only place in the world where parishioners did not pay a tithe to their parish priests.[75] Two years later he stated that the problem at Louisbourg was not in convincing visiting mariners to make donations to the church, it was in overcoming the parsimony of the residents of the town. Saint-Ovide explained to the minister that the inhabitants gave nothing "for all the trouble the curés take to administer the sacraments, perform their curial functions and instruct their children in their faith."[76]

Saint-Ovide was exaggerating when he wrote that none of the residents paid the voluntary tithe; some of them did .[77] Yet he was obviously irritated at the many who did not pay, or else who paid only in part or in a [...46...] grudging manner, The attitude which he decried seems to have been basically the same one Commissaire-ordonnateur Mézy had noted a decade earlier; that is, the inclination of the colonists to put their own interests ahead of those of the community at large. Needless to say the people of Ile Royale were not the only ones guilty of such self-interest and lack of charity when it came to giving to the church. During the same era, royal officials and bishops in Canada were repeatedly complaining about the reluctance or failure of the parishioners there to pay the tithe.[78]

The controversy over the payment of the tithe began in 1730 and lasted until 1733, when it was decided to give back to the visiting ship captains their positions of prominence in Louisbourg's religious processions. That suggestion, the obvious solution, was first put forward by the commissaire-ordonnateur.[79] By October 1733 an acceptable compromise had been reached, whereby "the most senior Captains" were given the right to carry two flambeaux (torches or candlesticks) in the processions.[80] As for Zacharie Caradec and his plans for the parish, the damage had been done. Caradcc had alienated so many people in Louisbourg that it became essential that his provincial recall him to France.[81] In mid- 1733 a friar named Hippolyte Herp was sent to the colony to assume the duties as curé of Louisbourg and superior of the Récollet mission there. Caradec retained his titles as commissaire and vicar-general until 1734, when he returned to one of the Récollet convents in Brittany."[82] ...

[...56...] ... The conditions in which the Récollets lived and worked during the 1750s were far from ideal. Chérubin Ropert, who arrived in the colony in June 1752, described Louisbourg as a "place of exile." That assessment was undoubtedly coloured by the unsatisfactory state of his accommodation. The Récollet residence was "completely dilapidated, without provisions"; the order had to rent another house in town (for 400 livres), in which Ropert had a room in the attic that was "exposed to the four winds." Moreover, there was not even a bed for him on his arrival; "luckily for me I had bought one in France" before departing. Other essential purchases made before the voyage included a mattress and cover, three pairs of stockings, two pairs of shoes, two pairs of breeches, six pairs of undershorts, twelve handkerchiefs, a coat, a cap, and three tunicles. [129]

The poor housing conditions in which the Louisbourg Récollets seem to have lived, combined with the by then customary personnel shortages, must be taken into account when one reads the criticism of the Ile Royale friars during the 1750s. The loudest complaints were made by Abbé de l'Isle-Dieu, the bishop of Québec's vicar-general for New France. Reflecting the pessimism he felt about the situation of the church generally in New France, Isle-Dieu almost never found anything praiseworthy about the Récollets. Indeed, after they returned to the island in 1749 the vicar-general wrote to his bishop that it was probably unreasonable to expect improved behaviour from the friars.[130] Shortly thereafter, he claimed that the Récollets had met his worst expectations. ...

[...64...] ... From 13 June to 19 July 1758 there were numerous baptisms and burials in the town.[162] On 9 July a house belonging to the "monks" was hit by a cannon shot but no one seems to have been injured. [163] ...

_________

...

12 AN, Colonies, C11B, vol. 5, fols. 300-5, Conseil de Marine, 28 janvier

1721, au sujet de la lettre de Mézy du 3 décembre 1720.

13 Ibid., fols. 151-51v., Saint-Ovide et Mézy, 7 décembre 1721.

14 Ibid., C11C, vol. 15, fol. 210, Saint-Ovide et Mézy, 7 décembre 1721.

15 Ibid., B, vol. 44, fols, 557-9v., Mémoire du Roi à Saint-Ovide et Mézy,

juin 1721; ibid., vol. 45, fols. 925-9, Ordonnance pour l'établissement du

droit d'un quintal de morue, 12 mai 1722.

16 Ibid., C11B, vol. 6, fols, 251-1, Mézy, 25 novembre 1723.

17 Ibid.; ibid., fols. 152-62v., Saint-Ovide et Mézy, 29 décembre 1723.

18 Linda Hoad, "Reports on Lots A and B of Block 3" (June 1971), 2, AFL;

AN, Colonies, C11A, Vol. 126, fol. 237 (in the larger numbers), Estat des

Emplacements, 1723, no. 3, Lot D.

19 AN, Outre Mer, GI, vol. 406, reg. i, baptême du 12 avril 1724. The curé

wrote that the child in question had been "baptisé dans notre chapelle

conv. de Ste. Claire."

20 Hoad, "Report on Lots A and B of Block 3," 2.

21 Blaine Adams, "The Construction and occupation of the Barracks of the

King's Bastion at Louisbourg," Canadian Histozic Sites: Occasional

Papers in Archaeology and History, 101.

22 AN, Colonies, C11A, Vol. 107, fols. 271-3, Mémoire à Maurepas, février

1736; Lyon's biography is in DCB 3: 413-4.

23 AN, Colonies, B, Vol. 65, fols. 3v.-4, Ministre au Père Maurice

Godefroy, 14 janvier 1737; ibid., fols. 445v.-6v., Ministre à de Brouillan

et Le Normant, 16 avril 1737; ibid., C11B, vol. 20, fols. 222-3, Verrier,

2 janvier 1738; ibid., fols. 111-2, Le Normant, 26 janvier 1738.

24 Ibid., B, vol. 66, fols. 297-8, Ministre à Bourville et Le Normant, 6

mai 1738; ibid., C11B, vol. 20, fols. 52-9, Bourville et Le Normant, 21

octobre 1738.

25 RAPQ, 1936-7, 435, Isle-Dieu à Pontbriand, 28 mai 1756; see also RAPQ,

1936-7, 397, Isle-Dieu à Pontbriand, 25 mars 1755.

26 Schmeisser, Population of Louisbourg, 56. During the 1730s in

Québec, when its population was between 4,000 and 5,000 inhabitants, there

were complaints that its parish church (which was the cathedral for the

diocese, built in 1666) was too small for the town. The governor and

intendant proposed that a second parish church be erected. Needless to

say, the cathedral at Québec,

whatever its size limitations, was far larger than the chapels which were

used as the parish church in Louisbourg. Gosselin, L'Église du Canada, 2:

125-6, 337nl.

27 AN, Colonies, C11B, vol. 24, fol. 319, Saint-Ovide et Le Normant, 10

septembre 1736; ibid., vol. 31, fols. 6-6v., 27 janvier 1751; ibid., fols.

7v.-8, 27 janvier 1751. The meeting of parishioners to decide what each

should contribute was the standard approach to church construction in

Canada. Jaenen, Role of the Church, 91.

28 AN, Colonies, C11A, vol. 56, fols. 180-1, Dosquet, 8 septembre 1731.

Dosquet also asserted that Niganiche generated more than 1,000

écus

a year in parish revenue.

29 For studies of these two aspects of the colonial economy see Balcom,

"Cod Fishery of Isle Royale"; Moore, "Merchant Trade in Louisbourg"; and

idem, "The Other Louisbourg."

30 Hugolin, "Table nominale des Récollets," 92.

31 AN, Outre Mer, c; 1, vol. 406, reg. 1, 11, and III, parish records

entries for September and October 1724 when Le Dorz's name and title

appear for the first time.

....

45 Saint-Vaflier's description of the Récollets as reprehensible is in AD,

F-Q, 23 H 14, Lettre des Récollets, pièce 13, Saint-Vallier à Dirop, 15

juillet 1727. For other opinions of the bishop see AN, Colonies, B, vol.

50, fol. 535v., Maurepas à l'évêque de Québec, 13 mai 1727. Maurepas

mentioned that he had received five letters from the bishop written in

September and October 1726.

46 AN, Colonies, cl IB, vol. 8, fols. 104-6, Mézy, 5 décembre 1726,

....

65 In October 1742 a royal official in the town had it recorded in a local

case that he was acting on behalf of the "fabrique de I'Eglise paroissiaue

de cette ville a déffaut

de marguilliers." AN, Outre Mer, G2, vol. 198, dossier 168, De Par le Roy,

13 octobre 1742.

66 AN, Outre Mer, G3, pièce 132, Procès verbal de visite du grand vicaire

dans l'église de parroise à Louisbourg, 13 février 1730. The four laymen

who signed this document were most likely the marguillers. They

were DeLort (Guillaume), Carrerot (Pierre was identified as a warden in

1732), Daccarrette le jeune (Michel was identified as a warden in 1730,

1731, and 1732) and another whose name has not yet been deciphered.

67 For more details on this subject see the discussion in the next

chapter. The documentary sources are given in the notes.

68 Jaenen, Role of the Church, 85.

69 Frégault,

Le XVIIIE siècle Canadien, 139-40.

70 AN, Colonies, C11B, Vol. 11, fol. 22, Bourville et Mézy,

31 décembre

1730; ibid., vol. 12, fols. 22-4, Saint-Ovide, juin 1731; ibid., vol. 13,

fols. 24v.-5v., Mézy,

17 mars 1752; ibid., B, vol. 59, fols. 544-7, Ministre à Saint-Ovide et Le

Normant, 16 juin 1733.

71 Ibid., B, vol. 55, fols. 569-72, Ministre à Saint-Ovide et Mézy,

10 juillet 1731.

72 Ibid., fol. Iv., Ministre au Provincial des Récollets

de Bretagne, 9 janvier 1731; ibid., fol. 575v., Maurepas a Caradec, 11

jullet 1731.

73 Ibid., C11B, vol. 12, fol. 185, Caradec, 30 novembre 1731.

74 Ibid., B, vol. 57, fols. 773v.-4, Ministre à Caradec, 27 juin 1732.

75 Ibid., C11B, Vol. 12, fols. 23v.-4, Saint-Ovide, juin 1731.

76 Ibid., vol. 14, fol. 112, Saint-Ovide, 20 octobre 1733.

77 See for example the receipts for payment of the dîme in the accounts of

Anthoine Perré. AN, Outre Mer, G2, vol. 195, pièce 83, Partage des biens

de la succession d'Anthoine Peré, 1735.

78 Jaenen, Role of the Church, 85-90.

79 AN, Colonies, C11B, vol. 13, fol. 25v., Mézv,

17 mars 1732.

80 Ibid., vol. 14, fols. 27v.-8, Saint-Ovide et Le Normant, 10 octobre

1733; ibid., fols. 31-4 1 v., Saint-Ovide et Le Normant, 11 octobre 1733.

,

81 Ibid., B, vol. 58, fol. 47, Ministre à Godefroy, 2 juin 1733. The comte

de Maurepas' explanation of Zacharie Caradec's character flaws was spelled

out in a 1735 letter to the provincial of the Récollets de Bretagne. AN,

Colonies, 1B, vol. 62, fols. 37-37v., Ministre à Godefroy, 11 avril 1735.

82 AN, Outre-Mer, G1, vol. 406, reg. IV: Louisbourg 1728-38, fols. 49v-55.

...

129 AD, F-Q, 23 H 14, pièce 34

130 RAPQ (1935-6), 301, Isle-Dieu à Pontbriand, 4 avril 1750. The only

Récollet Isle-Dieu seems to have praised was Ambroise Aubré. See for

example RAPQ (1936-7), 356, Isle-Dieu à Pontbriand, 29 mars 1754.

...

162 Ibid., reg. III, fols. 1v-2v.

163 CTG, Manuscript 66, Journal de Poilly, 82.

...

Krause, Eric (Krause House Info-Research Solutions). Property Developments Fronting Rue Royalle And Rue D'Orléans (Including Rue D'Estrées And Rue Dauphine Fronting Block Thirteen) Louisbourg: 1713 - 1960. Unpublished Report HB701K72000 [2000-141] (Fortress of Louisbourg, August 21, 2000 (Revised December 11, 2004)) [For the complete report, click on the title]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HISTORICAL STREET

FRONTAGE CHECK LIST

PART ONE

AN INTERPRETATION OF BUILT EVENTS - CONSTRUCTION DETAILS BY LOT, BLOCK, AND

STREET (1713 - 1960)

(I)

INDIVIDUAL LOT DESCRIPTIONS

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(A) FRONTING RUE ROYALLE

Fronting Rue Royalle, the following development occurred:

BLOCK THREE

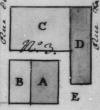

LOT C

(a) First Significant Fronting Rue Royalle Description: - 1718: Concession

(b) Concession Date(s): - June 27, 1718

(c) Frontage Dimension(s): - 123 pieds: 1734

(d) Frontage Construction Date(s)/Dimension(s): (1) Phase One - October 23, 1721:

Mature Construction Footprint - The face of an L-shaped building [October 23, 1721] - with a feature in the street attached to its western portion - and, to the east, the face of a yard with the face of a gateway next to the building

(2) Phase Two - Pre-1767:

Mature Construction Footprint - The face of a garden [Pre-1767], at the corner of Rue Royalle and Rue de l'Étang

(e) Building Type(s):

(1) N/A - On a stone foundation

(2) Garden

(g) Function(s):

(1) Récollet presbytery (a.k.a. hospice or couvent)

(2) Garden

(f) Notable Event(s):

- In 1721, a stone foundation was laid with possible foundation medals

- In 1723, a portion of the building was completed

- By 1734, construction had encroached upon Lot D to the west

- An empty lot replaced the presbytery during the English 1745-1748 occupational period. The building may have been destroyed during the siege.

(h) Last Significant Feature Description: - 1767: A garden

(i) Block Report: - N/A

LOT D

(a) First Significant Fronting Rue Royalle Description: - 1717: Proposed location

(b) Concession Date(s): - 1723: King's memoir

(c) Frontage Dimension(s):

- 60 pieds: 1723

- 52 pieds: c 1730-1734

- 42 pieds: 1734

(d) Frontage Construction Date(s)/Dimension(s): (1) Phase One - October 23, 1721:

Mature Construction Footprint - The stone foundations of the gable end of a building [October 23, 1721], at the corner of Rue Royalle and Rue St. Louis

(2) Phase Two - c. 1746:

Mature Construction Footprint - The face of a small building [c. 1746], set back from Rue Royalle - with the face of property to the east and west of it

(3) Phase Three - By 1767:

Mature Construction Footprint - The face of a building [1767], at the corner of Rue Royalle and Rue St. Louis

(e) Building Type(s):

(1) Rubble stone

(2) N/A

(3) Wooden

(f) Function(s):

(1) Proposed récollet parish church

(2) N/A

(3) House or shed

(g) Notable Event(s):

- A stone foundation was laid, with possible foundation medals

- The building was considered to be under construction as late as 1723, though work had actually been suspended earlier

- On May 6, 1738, the project for building a large parish church was officially put on temporary hold. At some point, a much smaller building was raised in its place.

- By 1767, the house was uninhabitable. In 1768, the shed was declared to be old.

(h) Last Significant Feature Description: - 1768: A standing building

(i) Block Report: - N/A

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(II)

GENERAL BLOCK DESCRIPTIONS

BLOCK THREE

(a) First Significant Block Description: - 1717: Initial survey

(b) Concession Date(s): - N/A

(c) Block Dimension(s):

(1) Rue Royalle

(i) c. 25 toises: 1717

(ii) 27 toises 2 pieds: 1722

(iii) 27 toises 3 pieds: 1734

(d) Function(s): - Religious

(e) Notable Event(s):

- Initially, in Rue Royalle - opposite the Block and towards the east - a stream crossed the street, and, opposite Rue de l'Étang, emptied into the rear of Block Four

- Initially, in Rue Royalle - opposite the Block - the side of a hillock also existed

- The block dimensions were finally settled on October 15, 1734

- In 1767 and 1768, the block was well illustrated

(f) Last Significant Block Description: - 1767